Our comprehensive report on surveillance in Canada is available. Download it here.

Trend 1 – The Normalization of Surveillance

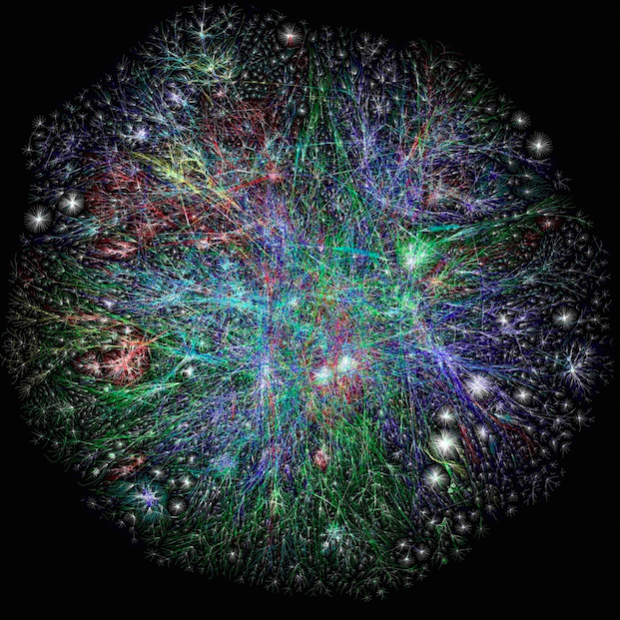

Surveillance is consistently front-page news, and it raises some of the most pressing social, political, and ethical questions of our day. At the same time, surveillance is not new. Interpersonal face-to-face scrutiny is an inherent attribute of human coexistence, and organizations also have a long history of using surveillance for various purposes. However, we are at a historic turning point in terms of the expansion, intensification, and integration of surveillance measures. There is simply more surveillance occurring today, and the surveillance systems we now use have unprecedented abilities to see more, penetrate deeper, and forge more novel connections than has ever been the case in the past. This expansion and intensification is perhaps the most notable and unsettling development in the dynamics of surveillance and monitoring.

Two examples drawn from different institutional settings help to illustrate the scope of contemporary surveillance. The first comes from the business world and concerns the company Acxiom. An international data aggregator, Acxiom collects personal information about people, including Canadians, from different sources, which it then sells to corporations and political groups that use it for marketing and campaigning. The information that Acxiom collects is extremely diverse, including data as familiar as name, address, and telephone number. The company also amasses and sells more sensitive data, such as marital status, family status, age, ethnicity, the value of your home, what you read, the type of car you drive, what you order over the phone or Internet, where you vacation, your hobbies, any history of mental illness you might have, your patterns of alcohol consumption, and so on. Even before the advent of social media, the quantity of information held by Acxiom was immense—roughly equivalent to a stack of King James Bibles fifty thousand miles high.1 Given the popularity of applications like Facebook, which have revolutionized the amount of personal data available to aggregators and other organizations, that amount now massively under- represents the volume of data that Acxiom processes.2

The second example pertains to the collection and analysis of intelligence information from electronic sources such as cellphones and the Internet for national security purposes. Since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Canada and the United States have increased the amount of intelligence sharing between our countries. Although the process remains highly secretive, we get occasional glimpses of the almost unimaginable amount of information that is being collected. James Bamford reports that by 2015, the American National Security Agency expects to be processing information at the astounding level of the yottabyte: ten-to-the-power-of-24 bytes.3 Translated to the print world, this equals one septillion—that is, one trillion trillion—pages of text. In 2011, the combined space of all computer hard drives in the world did not amount to one yottabyte.

These two illustrations involve surveillance conducted with the aid of computers, often referred to as “dataveillance.” To further round out the surveillance picture, however, one would also have to include technologies such as video cameras, drones, drug testing, automated licence plate readers, smartphones, and biometrics (that is, technologies that identify individuals on the basis of a biological characteristic). The most familiar way to identify someone through biometrics is fingerprinting, but biometric systems can now identify people based on their DNA, facial structure, hand geometry, voice, way of walking, and eye retina or iris patterns. Together, all of these phenomena are producing, and will continue to produce, sweeping transformations in almost every realm of existence, including commerce, warfare, science, international security, health, child care, work, and the formal and informal mechanisms we use to encourage people to conform to societal expectations and follow societal rules (often collectively called “social control”).

Not long ago, we might have believed that surveillance was confined to the world of espionage or directed primarily at criminals. Such assumptions were never particularly accurate given the long-standing use of urveillance in realms such as work and commerce, but today, it is easier to recognize that surveillance has become an inescapable reality for almost everyone. Being monitored is increasingly the trade-off for reduced prices or improved services. It is also not just a visual phenomenon, since monitoring now involves the massive use of electronic data. In fact, many of us provide some of this data willingly because doing so makes our lives more convenient.

This vignette provides a glimpse into how surveillance has become a part of the everyday routine for both Canadians and others in industrialized societies. Read the full trend in the free download of the Transparent Lives: Surveillance in Canada book.

- 1. Robert O’Harrow Jr., No Place to Hide (New York: Free Press, 2005).

- 2. Regarding social media and personal data, see Daniel Trottier, Social Media as Surveillance (London: Ashgate, 2012).

- 3. James Bamford, The Shadow Factory: The Ultra-Secret NSA from 9/11 to the Eavesdropping on America (New York: Anchor, 2009).